- Home

- Liza Nelson

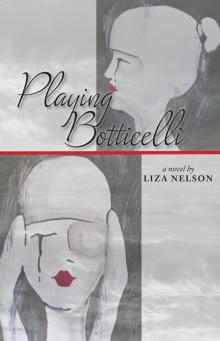

Playing Botticelli: A Novel

Playing Botticelli: A Novel Read online

a novel by

LIZA NELSON

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2000, 2015 by Liza Nelson

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nelson, Liza.

Playing Botticelli / Liza Nelson.

p. cm.

ISBN 987-151911-5904

I. Title

PS3564.E4676 P57 2000 99-047292 CIP

813’.54—dc21

For Jacob and Rosie

Acknowledgments

Sara Nelson, without whose encouragement, support and occasional needling I doubt I would have finished this book;

Pam Durban, teacher and friend;

Trish Hall, Pamela Harrison, Hilary Rosenfeld, Virginia Parker, Amelia Cook, Anne Lawson-Beerman, Nena Halford and Vinnie Rosenzwieg, each of whom succored my writing in her own way, whether through correspondence, conversation or chocolate;

Alice Martell, my agent, for her enthusiastic faith even when mine was wavering;

Laura Mathews, the editor every novelist dreams about;

and Rick Brown for sharing it all.

One

One

AUGUST 28, 1986

Well, this summer is over. Kaput. Finis. Down the tubes. Extinct. All gone. The end.

As far as I’m concerned, anyway.

It shut like a book this afternoon. One minute I was full of August, easing my way down Highway 12, windows down, music blasting, the hot wind whipping in thick ribbons against my neck. The next minute I was chilled to the bone.

To the bone.

I’d been at work. The teachers come back for pre-planning in a week, and I want no hassles from middle-aged women having nervous breakdowns because their chalkboards are dusty or their windows won’t open. Life is too short and art is too long. Being a janitor—excuse me, custodian—is not exactly my life’s work. I am an artist first, but I have to earn a living. If I were by myself it would be one thing, but with a daughter to feed, clothe, educate and all the rest, I’ve had to make my compromises, though fewer than most people, I’m glad to say. Bourgeois excuse, someone would have accused me in ’68, back when the revolution was at hand. I’m kidding, sort of. Besides, I take pride in being a woman with Mechanical Skills, as Gulfside Elementary’s esteemed principal Granger Morris would say.

It must have been around three o’clock when I finished painting the cafeteria ceiling an incredible azure blue, and I’d added the Pleiades and a few other constellations as my signature. There are ways to do a job, and then as Daddy used to say, there are ways to Do a job. Old Grange could always ask me to repaint it, but he never would. Certain teachers might complain among themselves, but not to me directly. A good janitor has clout, especially in a school with as few resources as Gulfside.

I gave the floor a good once-over with the mop, packed up and started home to Point Paradise. I was singing along with the oldies station out of Tallahassee, “Don’t you want somebody to love? Don’t you need somebody to love?” People have told me I look a little like a redheaded Grace Slick, or they used to when I lived where people had actually heard of her.

Then the news came on. Out in California, land of the seasonless season where all our dreams and nightmares bloom, a DC-9 and somebody’s private jet had tried to thread the eye of the same needle.

“Eighty-one dead,” according to the disembodied radio voice.

Just the idea. One minute you’re looking out one of those little curved windows feeling godlike, casting your shadow across the earth; twenty seconds later you’re bone chip and seared skin pierced with metal. Unless you’re on the ground looking up, thinking what a pretty pattern those two planes make flying so close overhead, until the sky bursts wide open to surround and lift you up toward the deafening wreckage. Toward heaven, if only it existed.

Of course, people have been blowing up all summer, the innocent with the guilty. Not just in planes. In buses, in restaurants, in department stores. Wherever a bomb can be stowed. Frankly, I can handle the concept of terrorism. At least someone means death to happen. If I’m going to be blown away, I’d rather spend my last millisecond thinking I’m dying for a cause, even some idiot’s insane idea of a cause that I find morally repugnant, than cursing the underpaid, undertrained air traffic controller, and probably a scab strike breaker at that, who has botched the job.

I’m willing to argue the point. I’m always willing to argue. As I’ve told Dylan over and over ever since she was a little girl, it’s bad politics to accept the authority of an idea until you’ve examined both sides. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying terrorists aren’t scary people doing evil things. But let’s face it, terrorists usually exist in the first place because some government screwed up, maybe months ago, maybe generations, maybe centuries ago. Maybe it was on purpose or maybe it was just a misjudgment on the part of an individual in some government department who set in motion the series of reactions, first to last, that led to the creation of people so angry and hopeless they’d commit desperate mayhem.

Not that I want to get into heavy political second-guessing. When I settled here, I pretty much left politics behind. That was the point of moving us to the edge of nowhere in the first place.

I’m out of the loop as they say a lot these days in Washington. Me and Vice President Bush. I mean who in their right mind wants to be in the loop? We thought Vietnam and Tricky Dick were bad, but the sixties were nothing. Let’s face it, we’re stuck in the middle of a decade that is spiritually pure shit, and Ronnie Reagan, with all his crummy little wars that keep breaking out on our collective chin, is leading the way.

Shit. Shat. Shitty. Wash my mouth out with soap. Nice girls and ladies do not talk that way around here, not that anyone would include me on her list of Esmeralda’s nice ladies exactly, and not that I care. In any case, I do love the word. “Shit” has to be the quintessential female expletive. “Fuck” and “damn” are basically masculine, don’t you think? Hard and sharp. “Shit” has the same number of letters but it’s slower to say, softer across the tongue. A nice, nasty contradiction. Plus there’s the mud pie in your eye against all those nice-nellyisms, like “ca-ca” and “poo-poo,” our mothers taught us to use to keep us proper.

I mean really, in my deepest heart of hearts, I’m still twelve years old, the vinegar sting of my mother’s slap hot on my cheek, pickle juice pooling at my bare feet that are pink from the blood trickling down my ankle where a glass sliver has lodged.

“Oh shit,” was all I said when the jar hit the linoleum.

“Judy, please!” There was a splatter of small dark stains down the front of my mother’s cashmere sweater. “I can’t stand it when well-brought-up girls say that word.”

The s-word. I was barefoot for God’s sake and there was glass everywhere and that was all she could think about. Of course, now that I’m a mother I’ll give her the benefit of a doubt. She could have been overwrought about something unconnected to me: the bad perm she got at the beauty parlor; trouble she was having getting the household checkbook to balance; Daddy coming home late from his insurance office yet again without calling. No matter. The devil had me by then. I laughed in her face and said it twice more, louder. That’s when she slapped me, hard. Another in a series of intimate moments between Mom and me.

Don’t get me wrong. I do not hate my mother. We talk almost every month. When she closed up t

he house in Connecticut seven years ago, I flew up to help her pack. The last time I was on a plane by the way. Since then, once or twice a year I drive Dylan— although she’s getting old enough to send alone—to Hilton Head, where Mother has a condo with Jack, whom she refers to discreetly as her special gentleman friend. A perfectly nice man, Jack.

No one would ever have dared to describe Daddy as a nice man. That’s what I loved about him, even during those two and a half years we didn’t speak because he had decided I could not be his daughter Judy Blitch if I was also an unwed mother living in a commune “with a bunch of long-haired, commie bastards” and calling myself Godiva Blue. “Jesus Christ, you sound like you’ve turned Negro. If you’ve got to change your name, why not call yourself Virgin so we could all laugh at the joke?” Daddy never did mince his words.

Mom minces, dices and arranges on a platter with parsley and radish hearts every time she opens her mouth. As I said, I do not hate her or resent her or even dislike her any more. As I said, we talk on the phone with a certain regularity. But let’s face it, all the phone calls in the world will not change the fact that we simply do not connect. She hasn’t the slightest inkling what I’m about, never has.

She loves Dylan of course. Not that she wanted me to give birth to her—as if I had an alternative at the time—but once Dylan was born, Mom couldn’t have given her up any more than I could, I’ll hand her that. She has more or less adjusted to the terms of my motherhood. Her great joy is sending along articles she’s clipped from earnest women’s magazines about single mothers and how they cope. Coping is one of her big themes. She does not believe I am coping well. Of course, she believes coping is a good thing: make do, stiff upper lip, stoic forbearance, the Puritan spirit at work. What in her life, aside from Daddy dying over all those pain-filled months, has required coping I am not sure, but I don’t bother to quibble because basically she’s right. I do not cope.

I am against coping on principle and I tell her so. Coping is an acceptance of less than you want. I expect more and don’t mind doing what it takes to get more. That’s why I hammered and forged and sculpted until I built the life I wanted. And when I decided I needed to earn a living and find a job, I did not simply cope. I made the job fit me, not the other way around. Of course, that choice of jobs remains beyond my mother’s comprehension. Needless to say, she never tells anyone in Hilton Head how I earn my living, and she can’t understand why, if I’m going to call myself an artist, I choose to live in Esmeralda, where she’s never been, instead of some overdeveloped artist-slash-tourist colony like the Vineyard or Greenwich Village.

“There are such limited opportunities.”

“You mean to meet men.” Men I can live without, as I have shown my entire adult life. Men are generally what I don’t want to meet, and if Esmeralda has few to tempt me, the better off I am here. But I bite my tongue. My unwritten rule of etiquette states that if she’s paying for the call, I try to avoid out-and-out confrontation. “Try” is the operative word.

“Not only men. Educated people.” That cute little hurt in her voice could not be louder and clearer if she were standing next to me in the room shouting through a bullhorn. “And what about Di?” She loves calling Dylan “Di,” as if she were named for Princess Diana, although, of course, Dylan was born long before the royal wedding. “What kind of education can she get there? Do they even have advanced-placement classes at the high school?”

“Dylan is happy.”

“So you say.”

I bite my tongue again. Dylan not happy? We have an almost perfect life. Not almost. Perfect. We play together, we create together. Dylan has never been merely my daughter, the way I was my mother’s daughter, a responsibility to give birthday parties for and drive to dancing classes. Dylan is a mind in formation, a spirit I am helping to shape. She goes to the local, admittedly mediocre school, but I have been her primary teacher. I don’t say it hasn’t become a challenge lately, now that the demons of adolescence have begun to circle. She can be moody and a little prickly at times, but not like other girls with their parents. Our relationship is different. Being Dylan’s mother is as intrinsic to my wholeness as a woman and an artist as being my daughter is intrinsic to her wholeness. Dylan, as much as myself, is the beneficiary of my quest for perfected vision.

That is what life is all about, isn’t it? Seeing true and clear to the core, so that you know the essence of a thing despite the detritus. When we happened into Esmeralda ten years ago I was just beginning my search, trying to piece together the elements of a life that would allow me to slough off all that garbagey stuff that clings to most people, women especially. Most have no vision so they are trapped in what they call their lives—narrow alleyways cluttered with all the petty trivia of television, office politics, bill paying, dating. Those dancing classes and birthday parties that kept cornering my mother and me in my childhood. The prosaic routine of domestic dependency. I wanted more. I wanted to inhabit my space in the world as I pleased.

So after Daddy died, I turned the twenty thousand dollars he left me into traveler’s checks, over my mother and her lawyer’s strenuous objections. Then I loaded all our worldly possessions into the back of Miranda, my VW bus, and took off, clutching a map of America’s back roads. Dylan was barely five, but she was a fine traveling companion for those three weeks, enthusiastic most of the time and surprisingly patient through the inevitable long stretches. I had not planned to stop in northwest Florida, but I fell in love with that barely visible line in the distance where sky and sea meet, how the roots of the scrub oaks dig in and take hold in the sandy soil. The spiky leaves of the palmettos. All that gnarled resilience. When I saw the FOR SALE sign at Point Paradise I knew we were home. It was destiny. Walking the marshy shore and looking out across the cove to flat open water and empty sky, watching Dylan’s delight in the geckos and in the pelicans nesting on abandoned pilings, I knew this particular geography had been ripening for years while it waited for me.

Not that people hadn’t stood there before, but no one who counted. Only a typical Florida land developer with King Midas dreams. Back in the fifties, he had cleared half the Point and built pastel bungalows to sell to rich retirees from Miami looking for a retreat from the sweltering heat of south Florida. Point Paradise was his name for the place and he gave each house its own title burnt into the lintel above the front door. Pelican’s Landing, Hibiscus Haven. I’ve always liked him for those names.

Then Hurricane Margaret-Ann hit, the same week his ad campaign was scheduled to run, the same week his workmen were under rush orders to finish installing the pink and aqua kitchens; the same week it so happens that my grandparents took me to Madison Square Garden in New York City to see a rodeo with Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, my heroes I’m not ashamed to admit. Shaking hands with Roy and Dale counted as the peak experience of my six-year-old life. When we came outside afterward, the skies had darkened to an ashy charcoal gray the color of the sleeve of my grandfather’s overcoat as he worked desperately to flag down a taxi cab. My first conscious sensory memory is the danger I could smell in the air, metallic and electric, smokey and moist.

My misguided get-rich-quick-now-bankrupt developer disappeared. I can see him, a small bald man who sweats through his linen suits, driving by his ruins one last time, his wife beside him, chipping off her nail polish and chewing her lip as they head north in a long-finned Cadillac whose back end sags under the weight of their hastily gathered possessions, the trunk’s mouth roped down into a half open grin.

Eight of the ten cottages had been flattened by the storm and never touched since. I used most of what was left out of my traveler’s checks—over half of my inheritance from Daddy—to pay cash for the twenty acres plus. God, it seems like so much land for so little money, but back then I was considered insanely fiscally brazen. Fiscally brazen, it sounds almost as bad as sexually promiscuous, which I was obviously considered by certain family members as well.

Rot and hibiscus overran

the place. Even Paradise, the cottage most inland and least damaged, was falling in on itself by the time I moved into it with Dylan. I stripped the cottage down to its skeleton and rebuilt. The folks at Ace Hardware and Henry’s Building Supplies were standoffish at first, as you can well imagine: Esmeralda, Florida, circa 1976: woman stranger who looks more than a little like a hippie coming around asking questions and buying supplies with traveler’s checks written on a Hartford, Connecticut, bank while her little girl hangs on her leg and refuses to smile or take even one piece of Chicklets gum. The raised eyebrows I saw the first afternoon Dylan and I walked in stayed raised for months, but eventually the guys got used to me. And I even got used to them, overalls, chewing tobacco, ma’ams and all.

I did my own plumbing and pretty much all my own electrical. It was a learning experience, that’s for sure. There is not one inch of surface, not a beam, not a nail hole, that I have not touched. Four rooms and a bath, that’s all we needed—plus my studio in the old toolshed—filled with serenity and order amid the chaotic beauty of the land. Point Paradise. The embodiment of my, Dylan’s and my, essential spirit.

And believe me, rebuilding Paradise was a spiritual act. I’ve been a studio potter, a weaver, a painter, even a glassblower. God, I had loved working the glory hole, but once I had Dylan I gave up my plans to go back. It was not a place to have a toddler crawling around. And I can’t say I ever had what I could call a sense of purpose until I worked on my house. Fishing wires through the walls, framing doors, smoothing Sheetrock plaster, I discovered the energy of space and time within the set boundaries of a ten-by-twelve-foot room. The quality of space. How life can expand within an imposed, purely spatial structure. It all goes back to vision.

That’s how I discovered my art. My boxes of wood—or clay or papier-mâché or whatever materials feel right—that I fill with my own constructions. My medium has become life enclosures. Not shrines. Not reliquaries. Though I like the spiritual nature of reliquaries, they’re still about what is past and dead. My boxes are worlds unto themselves, filled with the shapes and colors and textures of my visions. Vision. Your vision forms your life. The seeing beyond takes you into the within and vice versa. As in waking dreams. As in visionary. My college roommate and ultimate mentor, Evangeline Pinkston, talked a lot about making her own inspiration, but Evie was a genius, a real genius. All I have is a strongly developed attentive unconscious. And thank the gods I have that.

Playing Botticelli: A Novel

Playing Botticelli: A Novel